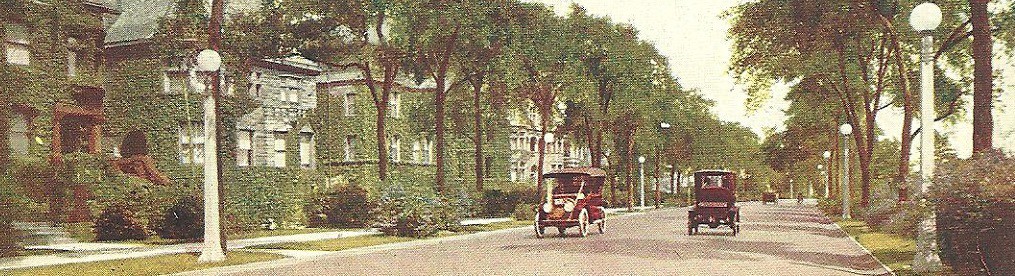

South Cottage Grove Avenue at East 51st Street

Opened 1869

As one of six large parks developed during the nineteenth century to serve the recreational needs of the people of Chicago, Washington Park, known as South Park until 1881, was one of the south side’s largest and most popular amusement spaces during the early twentieth century. Bounded by 51st and 60th Streets on the north and south, and South Parkway and Cottage Grove Avenue on the west and east, the park, then as now, occupied a total of 371 acres and was located approximately six miles south of the central business district.

The development of Washington Park on Chicago’s south side began in 1869. In that year, after years of lobbying on the part of prominent south side residents, the Illinois state legislature authorized the creation of the five-member, governor-appointed South Park Commission. The first order of business for the newly created commission was to secure funds for the purchase of new park land. Members of the commission envisioned the creation of at least two large parks to the south of the fashionable Hyde Park community, as well as a series of boulevards linking the parks to the central business district and the city’s other park systems. To that end, the commission authorized a $2 million bond issue to cover the cost of acquiring over 1,500 acres of land, including that which became Washington Park. The land acquisition process, however, did not go smoothly and costs soared as many landowners disputed the assessed value of their property, demanded a higher purchase price, and sued the commission when their demands went unmet. In 1871, the commission determined that the ultimate cost of land acqusition for the south side parks would surpass $3.3 million.

Despite these difficulties, the commission pushed ahead with its plans and, in 1869, employed New York-based landscape architects Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux to survey the Washington Park site and draft plans for its development as a formal recreational space. The architects proposed elaborate changes to the new park’s landscape. Their plans called for the planting of over sixty thousand new trees, the construction of a series of winding roadways, the laying of sewers, the filling in of wetlands, the opening up of a canal between the park and Lake Michigan, and the creation of a vast, pastoral meadow in the northern half of the park called the “South Open Green.”

Work on the park’s roadways and sewers had only just begun when the 1871 fire destroyed the commission’s offices in downtown Chicago, and with it most of Olmstead and Vaux’s blueprints. Construction resumed in 1872 under the guidance of landscape architect Horace Cleveland, who had collaborated with Olmstead on Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. The commissioners, concerned about the project’s escalating costs, instructed the architect to drop those parts of Olmstead’s plan that required drastic—and costly—alterations to the exisiting landscape. Accordingly, Cleveland eliminated plans for a canal and boat harbor at the southern end of the park and made development of the far less expensive “South Open Green” his main priority.

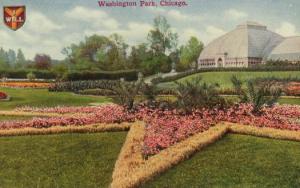

Washington Park, Conservatory and Flower Beds, ca. 1910

By the early 1880s, Washington Park had begun to take on the appearance of an urban pleasure ground. Several recreational lakes had been excavated. A music pavilion had been built for the hosting of summer band concerts. Sheep had been brought in to keep the grass on the park’s meadows clipped. And park officials developed a formal botanical gardens after receiving over three thousand donated packages of flower seeds and bulbs from cities around the world. Among Chicago’s parks, Washington Park and its gardeners became famous for the unique floral displays that surrounded the park’s plant conservatory. Later additions to the park included the 1881 refectory and the 1910 park administration building, both designed by Daniel Burnham’s architectural firm.

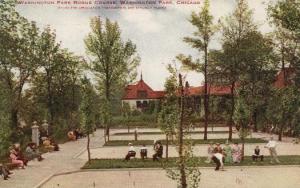

Washington Park, Administration Building, ca. 1910

In 1908, an observer enthusiastically described some of the park’s other amenities: “The Ramble, with its winding walks over artificial hills and ravines, through thickets and across bright open spots, is in direct contrast to the great common. Then there is the massive carriage house, built for the accommodation of the park horses and vehicles, which is a model of its kind, and near the large conservatory is a beautiful lily pond. Croquet courts, an archery range, horse speedway, fly casting accommodations, wading pool and sand court (for children) and a house to shelter lovers and the winter game of curling, are a few of the other attractions which place Washington in the list of the other democratic parks of the city.”

Washington Park, Croquet Courts, ca. 1910

During the late nineteenth century, park officials and privileged observers often described Washington and the city’s other large parks as democratic recreational spaces where citizens from all walks of life mingled and enjoyed the refreshing pleasure of an afternoon or evening outdoors. In reality, the majority of the park’s visitors, at least until the turn of the twentieth century, were fairly affluent. Better off Chicagoans dominated the scene, driving their carriages through the park on Sunday afternoons in a conspicuous show of their wealth and sophistication. Since they shared many of the same cultural tastes, park officials and the park’s privileged visitors rarely clashed over the best uses for park land.

Not until working-class residential districts expanded farther south in the early twentieth century did Washington Park become readily accessible to poorer Chicagoans, even though many families still did not have the resources to make anything more than an occasional visit. As the social composition of park visitors grew more diverse, the demands for park services and amenities became more varied. Working-class park-goers desired athletic fields and baseball diamonds, but such demands often conflicted with park officials’ vision of the park as a relaxing refuge from the competitive rigors of urban life. As the city grew, more and more Chicagoans used parts of Washington Park for purposes other than planners had intended. During the 1920s and 1930s, youth gangs frequently clashed inside the park, and Washington Park became one of many urban spaces where whites and blacks often clashed over the failure to acknowledge some invisible boundary between the races.

Today, Washington Park remains an important public amusement space for south side Chicagoans. The administration building is now home to the DuSable Museum of African American History.

Internet Resources

Photograph: Washington Park archery field, 1908 [Library of Congress]

Photograph: Four unidentified female archers standing in front of an archery target at Washington Park, 1909 [Library of Congress]

Photograph: Tennis players holding racquets over shoulders on tennis court, Washington Park, 1910 [Library of Congress]

Photograph: Tennis court, men and women playing in Washington Park, 1910 [Library of Congress]

Photograph: Anglers standing and sitting on a dock spanning a body of water in Washington Park, 1914 [Library of Congress]

Photograph: Archery meet, Washington Park, men and women participants lining up for meet, 1915 [Library of Congress]

Photograph: Three young women sitting in a rowboat in a body of water, Washington Park, 1928 [Library of Congress]

Photograph: Four young women sitting in a rowboat in a body of water, Washington Park, 1928 [Library of Congress]

Sources: A.N. Waterman, ed., Historical Review of Chicago and Cook County, vol. 1 (Chicago: Lewis Publishing, 1908), 228-230; A.T. Andreas, History of Chicago, vol. 3 (Chicago: Andreas Co., 1886), 167-172.

Image sources: “Washington Park, Chicago,” postcard, unknown publisher: #169C, n.d.; “Administration Building in Washington Park, Chicago,” postcard, V.O. Hammon: #1967, n.d.; “Washington Park Roque Course, Washington Park, Chicago,” postcard, V.O. Hammon: #2226, n.d.