West Roscoe Street and North Western Avenue

Opened 1904, closed 1967

For much of the twentieth century, Riverview Park on Chicago’s northwest side was one of the city’s most popular amusement destinations. Spread across more than 140 acres of land bounded by Belmont Avenue on the south, Western Avenue on the east, and the north branch of the Chicago River on the west, the park offered inexpensive amusements to work-weary Chicagoans. Every summer, thousands flocked to the park to enjoy its combination of thrilling rides, fascinating exhibits, cheap eats, interesting people, and cool evening air.

Riverview was the creation of William and George Schmidt, whose successful dealings in the city’s booming real estate trade provided them with the necessary capital to enter the amusement business. In 1900, they purchased what was then known as Sharpshooter’s Park at Belmont and Western Avenues. The park was the home of German gun club that shot at targets set up on an island in the middle of the river and hunted for game in the woods nearby. But the Schmidts often received complaints from the gunmen’s wives that the park offered women and children little in the way of entertainment while their husbands were busy shooting. Partly in response to such requests, the Schmidts looked for ways to expand their park’s variety of amusements and thus increase its appeal for entire families. In 1903, George Schmidt visited Copenhagen’s famous Tivoli Gardens while on a tour of Europe. Apparently inspired by the park’s beauty and variety of amusements, Schmidt returned to Chicago determined to turn Sharpshooter’s Park into a similar pleasure spot.

Riverview Park, Carousel and Aerostat Swing, ca. 1910

Riverview’s first season of operation as an amusement park was the summer of 1904. Although attendance during its first season suffered some from inadequate transportation services to and from the park, successive seasons drew ever larger crowds. The leading attractions during the park’s early years included a toboggan slide, a giant swing, the Old Mill tunnel-of-love ride, the water chutes, a carousel, a miniature railway, and a traditional midway featuring a variety of shows, games, and eateries. Daily performances by German bands were very popular as well, especially among the northwest side’s sizable German-American population.

Riverview Park, Refreshment Stand, ca. 1908

As the park matured and the public’s tastes in amusement shifted, Riverview’s owners constantly updated and improved the park’s attractions in order to lure patrons back year after year. This was especially true with the park’s most popular rides, its roller coasters. The park’s first coaster was the Scenic Railway, built in 1907. Though tame by comparison to later coasters, the Scenic Railway nonetheless thrilled riders with its gentle inclines and refreshing breeze. During the 1920s, as Chicagoans sought out ever more exciting physical sensations, the public demand for roller coaster rides increased and with it the number of coasters at Riverview. Among the new coasters constructed by park management during the decade was the famous Bobs. Built in 1926 at a cost of $80,000, the carefully designed coaster joustled its riders from beginning to end. Excessively sharp curves, shortened dips, low-riding cars, and clanking gears not only rattled riders’ bones, but intensified the illusion of the ride’s mechanical dangers and its seemingly life-threatening speeds. Other Riverview coasters included the Comet, the Blue Streak, the Pippen, the Jack Rabbit, and the Flying Turns, which was moved to Riverview in 1935 after Chicago’s Century of Progress Exposition, its former home, came to an end.

Riverview’s patrons visited the park for many different reasons. Many Chicagoans made their first visit to the park as children, either on a family outing or as part of a school or church group. As they aged, teen-agers and young adults continued to patronize the park, in part because its low prices made for an inexpensive date and because many of its rides afforded young couples the opportunity to hold one another tight or even steal a surreptitious kiss. Many of the park’s attractions were especially well-suited to the interests and desires of young men and women, including the jazzy Riverview Ballroom and the Riverview Roller Rink, where youthful roller-skating enthusiasts and members of the Riverview Roller Skating Club gathered to compete for prizes and make new friends.

Adults, to be sure, also enjoyed Riverview. Many who had first visited the park as a child returned with their own children, drawing pleasure from seeing the reactions of their own sons and daughters to the rides they had themselves so much enjoyed as chidren. Significant numbers of adults also came to Riverview as part of lodge or labor union outings, while on weekend leave from Chicago-area military duty, or with business associates in town for a convention or seminar. Even for older adults, Riverview, with its colorful midways, picnic groves, lively music, and passing crowds was an entertaining sight to behold and a leisurely way to pass a summer afternoon.

While Riverview’s management promoted the park as a family-oriented amusement center, there were those who wondered about its potentially demoralizing effects, particularly upon the hundreds of teen-agers and young adults who filled the park each night. Social reformers, as part of their efforts to clean up commercial amusements across the city, made frequent “inspections” of the park to assess how closely park management monitored the behaviors of their customers. Of particular concern to advocates of child welfare was Riverview’s ballroom, feared by some as a place where unchaperoned girls, if left to their own judgement, might be lured into a life of prostitution. Others pointed to occasional accidents on the park’s rides (see table below) as evidence that Riverview was not as safe as its owners and their publicists claimed. And during the early years of Prohibition, federal agents regularly raided the park and its picnic grove in search home-brewed beer. Park-goers, however, grew accustomed to the raids, sacrificing a token keg or two to the agents and then sounding an “all clear” for local residents and bootleggers to deliver the rest of the day’s illicit beer supply.

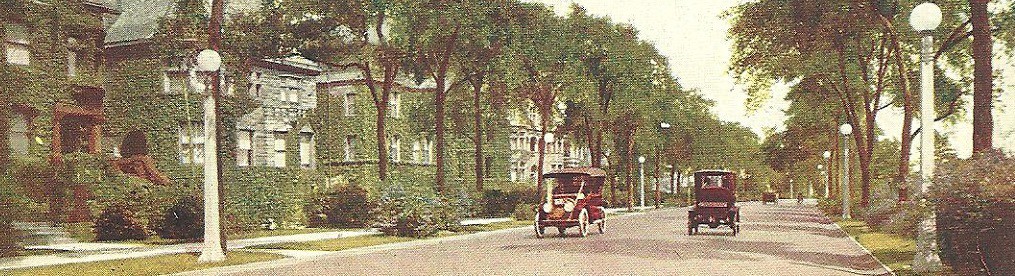

Part of Riverview’s success in attracting large crowds was due to its easy accessibility to public transportation. The front gate of the park was located within easy walking distance of five streetcar lines, including the lengthy Western Avenue line, which ran nearly twenty miles, making connections to thirty-five other lines along the way. In addition to the regular service, special “Riverview Park” streetcars provided rides to patrons coming from the Loop. While most park-goers journeyed to and from Riverview on streetcar, increasing numbers, especially by the 1930s, came by automobile. Confronted by a growing demand for parking facilities and fearful of losing customers unable to find a place to park their cars, Riverview management laid out a series of parking lots around the periphery of the park. Additional parking was provided by several privately owned parking lots located nearby.

An often unacknowledged factor in Riverview’s popularity during the early twentieth century was the informal exclusion of African-Americans from the park. Although there existed no official policy against the admission of blacks to the park, its distance from the growing black neighborhoods of the South Side and the sometimes discriminatory treatment toward non-white patrons on the part of booth and ride operators meant that only small numbers of black Chicagoans visited the park on a regular basis. In some cases, concessionaires exploited long-standing racial animosities by making blacks the subject of white amusement at the park. For many years, the African Dip was a well-known midway attraction, particulary among young white males eager to demonstrate their racial solidarity with other whites. Players of the game paid for the chance to dunk an “African” in a pool of water. Those who were hired to play the role of the “African” were encouraged to be as verbally abusive as possible in order to incite the animosities of white patrons and thus drum up additional business for the game. The Dip remained in operation until the late 1950s, when the NAACP pressured the park’s owners to remove the odious game.

Riverview continued to attract large crowds during the 1950s and 1960s. Chicagoans, as they had for most of the century, continued to enjoy the park’s exciting combination of wild rides, upbeat music, lively crowds, tasty eats, and cool evening air. Several factors, however, helped bring about the park’s closure following the 1967 season. The immediate causes were financial. Riverview’s operating costs, pushed upward by rising property taxes and increased maintenance costs on the park’s aging infrastructure, rose throughout the 1960s. When a developer offered to purchase the property from the Schmidt family, the deal was too enticing to pass up, particularly in light of what at the time appeared to be the growing unpleasantness of urban life in general. To have continued to have operated the park would have required the Schmidt family or some other group of operators to confront (and adjust to) the growing reluctance of white, middle-class families to live in the city and partake in its long-standing popular amusements. Not eager to share public spaces such as Riverview with African-Americans no longer willing to accept de facto segregation, the majority of white Chicagoans opted to abandon their familiar neighborhoods and entertainment centers and rebuild in the suburbs. Following the amusement park’s demolition, the site was redeveloped with a combination of light industry and various retail stores.

Internet Resources

Photograph: “Crowd of people standing at the entrance of Riverview Park for the Old Settlers Picnic,” Aug. 1905 [Library of Congress]

Photograph: “Lewis Ishrell walking with canes at the Old Settlers Picnic,” Aug. 1905 [Library of Congress]

Photograph: “Riverview Park, park goers riding the Bob #3 rollercoaster,” June 1915 [Library of Congress]

Photograph: “Riverview Park, park goers riding a merry-go-round,” June 1915 [Library of Congress]

Photograph: “Parkgoers riding a miniature train at Riverview Park,” 1916 [Library of Congress]

Photograph: “Spectators standing outside the monkey show booth at Riverview Park,” July 1916 [Library of Congress]

Sources: Billboard, 19 August 1911, 12; 24 May 1913, 18; 9 August 1913, 13; Variety, 27 August 1910, 19; 8 September 1916, 30; Chicago Daily Tribune, 1 June 1915, 6; 23 August 1916; 7 September 1924; 21 September 1925; 8 July 1932.

Image sources: “Riverview Park, Chicago, Western, Belmont and Clybourn Aves., Carasoul and Circle Swing,” postcard, n.p.: #365, n.d; “Refreshment Corner, Riverview-Park, Chicago,” postcard, Alba Novitas Schwarz & Co., n.d.