45 West Randolph Street

Built 1921

Architects: Holabird & Roche

The United Artists Theater was one of several large movie theaters that, for many years, helped make the Loop the city’s premier entertainment district. Located on at the southeast corner of Randolph and Dearborn Streets, the theater and its first-run movies attracted patrons from across the city.

Chicago’s United Artists Theater began as the Apollo Theater. In 1920, showman A.H. Woods, owner of the Woods Theater at the northwest corner of Randolph and Dearborn Streets, announced plans to build a new theater for plays and other live stage performances kitty-corner from the Woods Theater. Original plans called for a 1,600-seat theater topped by an office tower similar in size and height to that which rose above the Woods Theater. By the time construction on the new theater began in May 1920, however, Woods had decided not to go forward with the office component of the project. His decision to scale back the project most likely was the result of a downturn in the local economy following the end of the First World War. As a result, only the three-story theater was ever built.

During construction, there was considerable speculation about what the name of the new theater would be. According to reports, Woods had at first proposed naming the new theater the “Chicago.” But this upset the owners of another Chicago Theater on South State Street. In May 1920, word had it that the new theater would be known as the “McCormick,” in honor of the prominent local family which had agreed to lease the theater’s site to Woods for $96,000 a year. By December 1920, Variety announced that Woods now planned to call the theater the “Century,” but admitted that this too was in doubt. In the end, Woods dubbed the theater the “Apollo.”

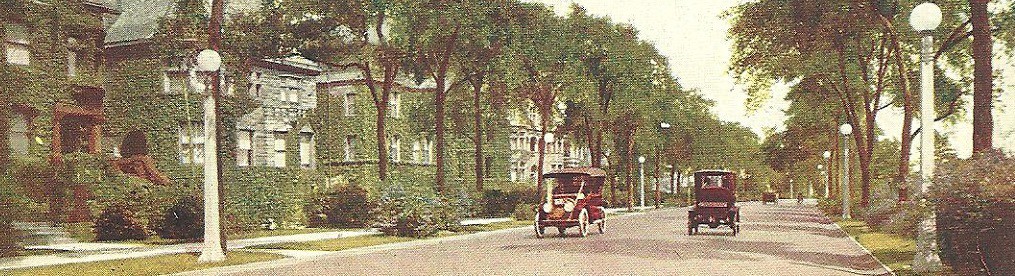

Apollo Theater, ca. 1922

The name “Apollo” befit the theater’s architectural style. To design the theater, Woods had hired the Chicago architectural firm of Holabird and Roche. The firm was one of the most prominent in the city and many of its early designs blazed new trails in the area of commercial and high-rise architecture. Among the more notable buildings designed by the firm before 1920 were the Marquette, Old Colony, City Hall-County, Boston Store, and Mandel Brothers Buildings. Perhaps in keeping with the ancient origins of the dramatic arts, Holabird and Roche designed the theater in the Greek Revival style. The rounded entryway, for example, featured four, two-story Corinthian columns. Along these lines, the architects designed the main auditorium to resemble a classical Greek temple, complete with murals of human figures in classical poses.

The Apollo opened in 1921. For the next five years, it operated as a legitimate playhouse. In 1927, however, Woods sold the theater to the United Artists Corporation, a motion-picture production and distribution company recently formed by leading Hollywood actors Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin, and Chicago’s Gloria Swanson. The theater was to become the debut venue in Chicago for all major United Artists releases. United Artists spent $900,000 to outfit the theater for movies and add the kind of glitz that would enable the theater to compete against the already popular Roosevelt and Chicago Theaters nearby. Company officials hired architect C. Howard Crane to draft plans for the renovation project. Following Crane’s plans, the interior of the theater was completely gutted. The new interior decorations followed an ostentatious Moorish-inspired style and featured black marble columns in the lobby, wall murals that depicted scenes from northern Africa, and a fancy, gold-leaf dome-like ceiling in the auditorium. Renovation of the theater continued into late 1927. On 26 December 1927, the new United Artists Theater opened for business, showing “The Dove” with Norma Talmadge and Noah Beery.

Like their counterparts at other Chicago movie palaces, the managers of the United Artists Theater employed a variety of special promotions to attract and entertain patrons. During the fall of 1928, for example, managers conducted straw polls on that year’s presidential contest by projecting slides of the candidates, Al Smith and Herbert Hoover, for applause. Smith, according to reports, won an average of five of every six showings. The theater’s managers often promoted new films with eye-catching displays in front of the theater. In 1929, they erected three promotional banners across the intersection of Dearborn and Randolph to promote the release of “Iron Mask,” starring Douglas Fairbanks. Some, however, doubted how effective such promotional stunts were. “Banner conflict among theaters,” observed a reporter for Variety, “is a serious serious matter locally. They’re getting so thick. The only time one can read them is when a couple of uninterested guys in overalls are hanging them up.”

Business at the United Artists slumped during the early years of the Great Depression. Average weekly revenues for the theater dropped from an estimated $31,100 in 1929 to an estimated $26,000 in 1930. By 1932, average weekly revenues dropped to an unprecedented low of $18,900. Burdened by declining ticket revenues and a lack of sufficiently enticing new films from Hollywood, the theater shut down entirely for a few weeks during the summer months of 1932.

In later years, control of the United Artists Theater passed from its namesake corporation to the Balaban and Katz chain, which eventually became part of Plitt Theaters. Plitt operated the theater during the 1980s. Ownership of the theater proved to be an enormous challenge for Plitt. Fewer Chicagoans traveled downtown to go to the movies during the 1980s than in earlier times, making it difficult attract enough paying customers for the theater to break even. Those who lived close by increasingly patronized the newer, state-of-the-art theaters built by Cineplex-Odeon and other theater operators near the Loop during the 1970s and 1980s.

Further complicating Plitt’s ownership of the theater were the actions of City Hall during these years. During Mayor Richard J. Daley’s time in office, city planners joined powerful real estate developers in drawing up plans for the redevelopment of several north Loop properties, including the United Artists Theater. The city’s plans called for all buildings in the designated zone to be condemned, demolished, and replaced by modern office towers. Aware that condemnation proceedings could be brought against the theater at any time, Plitt Theaters and its successor, Cineplex-Odeon, invested as little money as possible into the theater, cutting back on staff and maintenance. As a result, the theater fell into an even worse state of repair. As Henry Plitt, chairman of Plitt Theaters, complained: “The theater is in the middle of the North Loop redevelopment zone, and it is very difficult to get someone in there on a short term lease. We’re in a state of confusion.”

In 1985, Cineplex-Odeon acquired Plitt Theaters and took over operation of the United Artists. Two years later, with the redevelopment plan gaining steam, Cineplex-Odeon closed the theater. The last day of business was 19 November 1987.

In 1989, the United Artists Theater and most of the adjacent properties were demolished by the city. Redevelopment of the area, known to city planners as “Block 37,” languished in part due to misguided city planning and the collapse of the real estate market in the early 1990s.

Internet Resources

Photograph: Block 37, with United Artists Theater in foreground, ca. 1985

Sources: Variety, 6 Feb. 1920, 27; 23 April 1920, 31; 30 April 1920, 19; 17 Dec. 1920, 19; 8 Feb. 1928, 15; 10 Oct. 1928, 5; 20 March 1929, 76; 28 June 1932, 25; Chicago Tribune, 19 Nov. 1987, sec. 5, pg. 13A; and Ross Miller, Here’s the Deal: The Buying and Selling of a Great American City (New York: Knopf, 1996).

Image source: Holabird & Roche, Selected Photographs Illustrating the Work of Holabird & Roche (Chicago: Holabird & Roche, 1925), n.p.