Fun and Pleasure for Sale

Between 1900 and 1945, as the people of Chicago adopted new leisure and consumption habits, the city’s retail and entertainment industries boomed. Beginning in the 1910s and 1920s, movie theaters and dance halls opened across the city while downtown hotels launched numerous expansion projects. When the Depression hit and incomes fell, pennywise shoppers helped fuel the spread of discount department stores and other retail chains, even as other amusements, such as burlesque, vaudeville, and dime museums languished. The repeal of Prohibition in 1933 provided the city’s restaurants and night clubs a much-needed boost in business and the popularity of the big band performances between films helped larger movie theaters stay in the black. The Second World War returned full-fledged prosperity to the local entertainment industry, due in large part to the higher incomes of wartime and the spread of more carefree attitudes toward nightlife.

Cognizant of the potential for enormous profits, dozens of Chicago entrepreneurs invested millions in popular amusements. One such individual was Joseph Beifeld, who, in the early 1900s, acquired the moribund Hotel Sherman, renovated it, and turned its College Inn into one of the hottest night spots in town. Other notable impresarios of the period included Barney Balaban and Sam Katz of the Balaban & Katz movie theater circuit; William A.Wieboldt, founder of the Wieboldt department store chain; and J. Louis Guyon and Andrew Karzas, dance hall promoters. Significantly, many of the city’s leading impresarios were Jewish and drew upon their experience in Yiddish show business to help their new ventures succeed. They closely monitored audience reactions to performances offered in their show palaces and quickly dispensed with those acts that failed to win the approval of their patrons. During Prohibition, such careful attention to the ever-changing tastes of the host culture helped Jewish enterprises thrive, while their Irish and German rivals suffered.

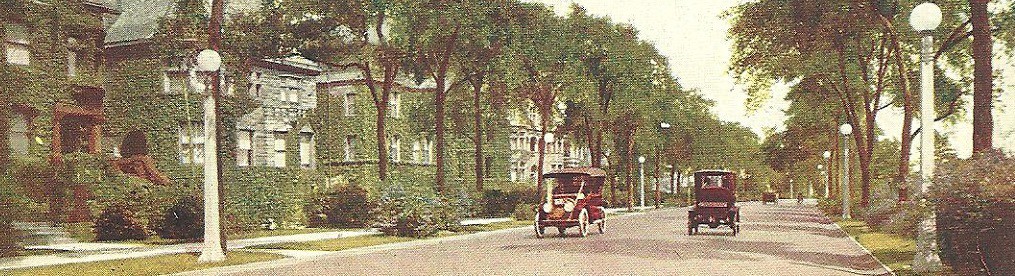

Geography also helped shape the spread of commercial amusements in Chicago. Certain localities within the urban grid emerged as leading retail and entertainment districts during the early twentieth century. Sometimes referred to as “bright-light districts” because of their concentrations of electrically lit windows and marquees, they typically developed wherever several forms of public transportation converged. The Loop was Chicago’s largest and most heavily patronized bright-light district, but its dominance slipped during the 1930s as new districts, such as Uptown, Englewood, and Woodlawn, expanded. No bright-light district was complete without at least one department store, several movie houses, and dozens of retail outlets, restaurants, and night clubs. The largest districts, particularly the Loop, sported hotels, dance halls, dime museums, tatoo parlors, pool halls, burlesque houses, brothels, and various other amusement venues.